WHAT we know of Margaret Catchpole, and her adventures around 1800, is mainly through the novel, first published in 1845, by the Revd Richard Cobbold, Rector of Wortham and son of Elizabeth Cobbold, employer, friend, and benefactress of the eponymous heroine. He must, therefore, have had first-hand knowledge of the story, but, putting it in novel form, took liberties, as novelists do, even inventing one of the main characters to provide the essential happy ending.

The book was a runaway success, and has remained part of Suffolk’s folklore ever since. It came to the attention of the composer Stephen Dodgson (1924-2013) through his wife, the harpsichordist Jane Clark, who lived in Suffolk. When Dodgson’s mother died and his father married a Suffolk farmer’s daughter, the two met and were married. Stephen came to love Suffolk, and Margaret Catchpole had been a favourite of his wife since she was a child.

It was, therefore, the obvious subject for a chamber opera commissioned by the local Brett Valley Society of the Arts, and the ideal librettist was to be Ronald Fletcher (not the BBC Light Programme announcer of blessed memory), who had in 1977 made use of Richard Cobbold’s account of 1860s Wortham in The Biography of a Victorian Village; in 1979, the opera, Margaret Catchpole — Two Worlds Apart, was first performed at Hadleigh in Suffolk.

Stephen Dodgson, particularly on the evidence of his considerable recorded legacy, is perhaps regarded mainly as a miniaturist, a composer of songs and instrumental chamber music and a remarkable quantity of music for the guitar. But he also worked in larger forms, including a Te Deum and Magnificat for soloists, chorus and orchestra, in whose first performances I was privileged to take part in the 1980s under the conductor Denys Darlow. The Te Deum has been one of my favourite works ever since, almost visceral in its impact, and with a clarity and integrity that is characteristic of all Dodgson’s music, as it was of his many broadcast talks and record reviews on BBC Radio 3.

So, what of Margaret Catchpole, last performed in 1989? This revival was keenly awaited, if the capacity audience at the Britten Studio in the Snape Maltings was anything to go by; and the audience’s reception was of uninhibited enthusiasm. The performance was recorded for future issue on CD.

The orchestra comprises a string quintet (including double bass), harp, and one each of flute, oboe, clarinet (doubling bass clarinet), bassoon, and horn. The 16 sung parts are taken by 15 soloists, and it is remarkable that every performer, singer or player, has music of a very high quality. On this occasion, there was without exception very fine singing and playing, with evidence that each part had been fully absorbed by the musician concerned.

This was a concert performance, but the singers adapted their costume to suggest their characters. Although there was a certain amount of movement and coming and going, they sang from behind music stands (not always the same music stand), but still projected their characters fully and, perhaps, more tellingly than if there had been a full staging. This is essentially a words opera, of which in Britain we have a tradition (for example, Geoffrey Bush’s Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime), very much suited to an intimate atmosphere, or radio or recording. Hence the suitability of the Britten Studio.

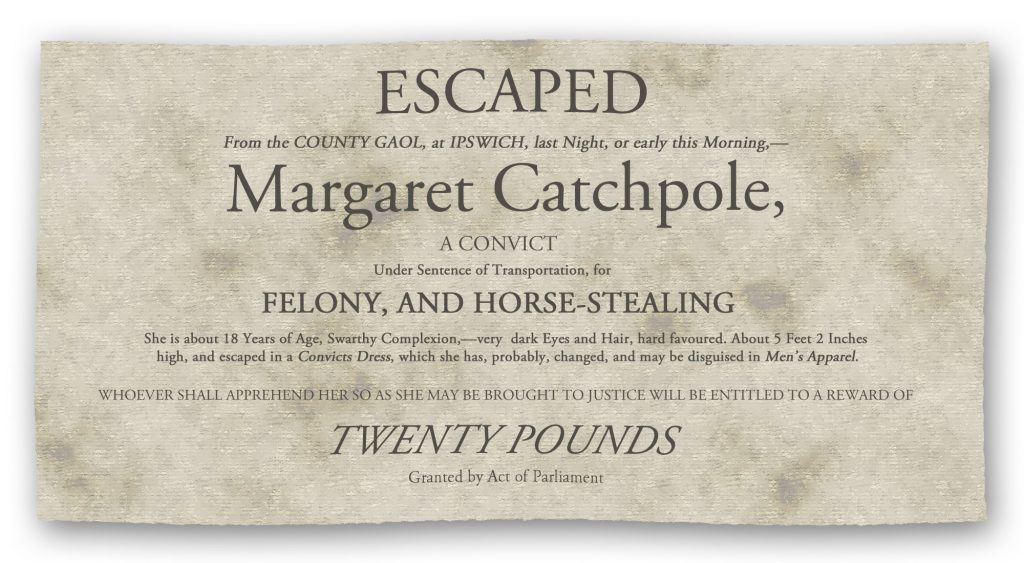

It is a long score — about two-and-a-half hours — perhaps too long to tell the essentials of the story, in which the heroine has two suitors, one of whom (William Laud) is a smuggler but, in Margaret’s eyes, a good man; the other (John Barry) is the honest son of a local miller, who loves Margaret, but she remains loyal to Laud. Laud’s companion John Luff (sung by the wonderfully villainous Nicholas Morris), having fallen out with his friend, plans to get rid of both Laud and Margaret and in an anonymous note persuades her to steal a horse, then a capital offence, for which she is brought to court, sentenced to death, but later deported to Australia. There she leads a blameless life and is eventually rediscovered by John Barry, miraculously transformed into the local Governor’s agent; he obtains a pardon for her from the Governor, and they marry and live happily ever after.

The Australian mezzo-soprano Kate Howden sang Margaret, a vocally demanding role that she delivered convincingly, except that in her soliloquy at the end the words needed to be clearer (or a printed libretto — which did once exist — provided). William Wallace and Alistair Ollerenshaw were Laud and Barry. But the supporting roles were equally interesting, in particular the tenor Richard Edgar-Wilson as “Crusoe”, a half-crazed fisherman who haunts the shore of the River Orwell and acts as a sort of Greek chorus, commenting on the action, foreseeing the future — very much a Peter Grimes type character in this opera that evokes Suffolk in a different but equally effective way from Britten’s.

Subtle movements and facial expressions, as well as magical singing from Edgar-Wilson, were among the most memorable and moving moments of the show. Diana Moore as Mrs Cobbold — genteel, reassuring, perhaps a little patronising, but ultimately Margaret’s best friend and ally; the veteran and always reliable Michael Bundy as Farmer Denton; Robyn Allegra Parton in the dual role of the Dentons’ servant Lucy and, later, Alice, the Cobbolds’ maid, in the latter role so knowing and sly; and the Swedish soprano Julia Sporsén as Mrs Palmer, Margaret’s employer in Australia, who does not appear until the fourth act, but gave a virtuoso performance in support of her employee.

All the instrumentalists played superbly and each was featured to illustrate particular moments. Orchestral interludes served effectively to provide atmosphere, but also to illustrate the passing of time and the changes of location. Julian Perkins conducted with unobtrusive authority. It was a memorable and hugely enjoyable (if slightly over-long) evening and, perhaps, the first of many new performances of this fine work by a fine composer and musician. The day before he died, Dodgson apparently told his wife: “We must do something about Margaret Catchpole.”

Garry Humphreys

Church Times

https://www.churchtimes.co.uk/articles/2019/19-july/books-arts/music/music-review-the-opera-margaret-catchpole